Tony Nikolovski and Olivier Walther

University of Florida

30 May 2025

Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis is strictly contained within linguistic and national borders. This makes it unique in a region where insurgencies tend to spread.

A localised insurgency

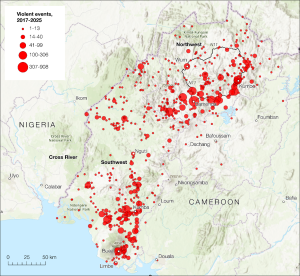

Since 2017, political violence in Western Cameroon has surged dramatically, driven by clashes between state forces and the separatist Ambazonia Defense Forces (ADF). Despite the growing violence, the conflict has largely remained confined within linguistic and national borders. According to ACLED, 99% of the violent events involving the ADF through mid-May 2025 occurred within the two anglophone regions that joined Cameroon in a 1961 plebiscite.

ADF-related violence is strongly clustered around Bamenda, the largest city and capital of the Northwest region, where 908 violent events having caused the death of 637 people have been observed since 2017 (Map 1). Another cluster of intense violence can be found further south, in the southwest region near Kumba, a city where 154 violent events were recorded. In both regions, the insurgency is heavily concentrated on the Cameroonian side of the border, leaving the Nigerian side largely unaffected.

Violence tends to be mostly rural and concentrated near transport infrastructure. The 350 kilometre ring road (RN11) connecting Bamenda to Kumbo and Wum is the most violent road in the whole of North and West Africa, with 757 recorded events since 2018. This is rather typical of rural and mountainous regions, where the sparse and poorly maintained transport infrastructure provides an ideal opportunity for insurgents to attack government forces and abduct civilians for ransom.

With an average of one victim per violent event since 2017, ADF-related violence is less lethal compared to other armed groups in West Africa. Over the same period, nearly three people were killed per incident involving the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM) in Mali, for example.

Fatalities in Cameroon mainly result from direct clashes between ADF and government troops, and violence against civilians, while air strikes and remote explosives are more extensively used by JNIM and the Malian government. This difference in tactics underscores the more localised nature of the Anglophone Crisis compared to the broader and more transnational threats posed by Jihadist groups.

Map 1. Violent events involving the Ambazonia Defense Forces, 2017-25

Stable patterns of violence

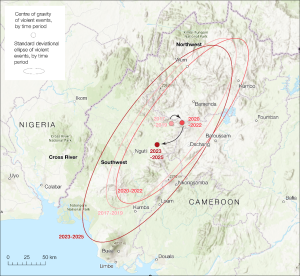

ADF patterns of violence are well-established in the region since the insurgency started. While the frequency and intensity of attacks have increased, the centre of gravity of the attacks has been rather stable over time. This location, which indicates the geographic centre of a group of projected points, was located between the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon from 2017 to 2022. This reflects the fact that the ADF insurgency is composed of two major hotspots, separated from each other by an area of relative low activity, from Nguti to the south of Bamenda.

In recent years, the centre of gravity has moved slightly southward to the Banyang-Mbo Wildlife Sanctuary (Map 2). The relative stability in the spatial distribution of ADF-related violence contrasts with the high mobility of the Boko Haram insurgency, whose operations have spread from west to east over the past 15 years across the Lake Chad region.

Map 2. Geographic focus and patterns of violence in the Ambazonian insurgency

It also appears that the same Cameroonian places are affected repeatedly. The pattern of violence, represented by “standard deviational ellipses”, shows that the ADF’s most intense activity has remained concentrated in a relatively small geographic area since the late 2010s. ADF’s events tend to be clustered in a narrow corridor following the Anglophone borders rather than extending towards francophone Cameroon in the east, or to Nigeria in the west.

The ADF’s contained approach to conflict contrasts with the expansionist strategy adopted by Jihadist groups such as JNIM, the Islamic State – Sahel Province, Boko Haram, or the Islamic State West Africa Province, who feel less constrained by colonial borders than separatist groups and have all become transnational in recent years, often following military interventions.

Why not go transnational?

The fact that ADF-related violence is almost exclusively observed in the anglophone regions of Cameroon does not mean, however, that insurgents are restricted by national boundaries. Political, linguistic, and cultural affinities are strong between the anglophone side of the Cameroonian border and Nigeria.

In 2021, the ADF announced an alliance with the Indigenous People of Biafra, a separatist group seeking independence from Nigeria. The ADF has also been able to smuggle weapons from Nigeria and recruit fighters without much military disruption from Cameroonian forces. The Anglophone Crisis has also led many Cameroonian refugees to relocate to Nigeria, especially in the Cross River State.

From the insurgent perspective, political and sociolinguistic ties with Nigeria makes containment close to Cameroon’s western borders a logical move. At its core, the ADF seeks secession, not a nationwide insurgency. Expanding into francophone regions would force the movement to cope with unfamiliar terrain and expose fighters who do not speak French to potentially hostile populations. Rather than seeking expansion, which would undermine their separatist identity, the ADF is concerned with targeting state symbols within Ambazonia.

Preventing the spread of violence beyond the anglophone regions poses a significant challenge for the Cameroonian government. A delicate balance will need to be found between military action and efforts to tackle the root causes of the crisis, such as political marginalisation. Prioritising dialogue and addressing grievances within the anglophone population could help mitigate further escalation, while avoiding measures that could exacerbate the conflict.