Photo by Arleen Wiese on Unsplash

Olivier Walther, University of Florida

Steven Radil, U.S. Air Force Academy

David Russell, University of Florida

9 December 2024

Political violence has fluctuated considerably since the end of the Cold War in Africa. Most of the current armed conflicts affect regions that were peaceful 20 years ago, while many of the regions in conflict 20 years ago are peaceful today. These variations suggest that the geography of conflicts expresses certain regularities over time. This spatial conflict life cycle, which we document for the first time, explains where, when and between whom violent events take place on the African continent.

Armed conflicts have their own life cycle

Armed conflicts pass through different stages throughout their existence, from the moment they emerge in some regions until they eventually end. In the early 2000s, much of the political violence was clustered in the Great Lakes region and along the Gulf of Guinea, before the war in Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, and Sierra Leone came to an end. Today, hotspots of violence have shifted to the Horn, the Sudan, and the Sahel, which are experiencing unprecedented levels of violence.

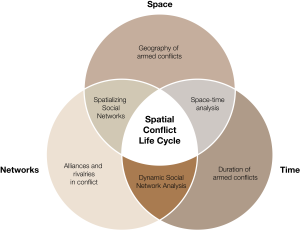

The concept of spatial conflict life cycle was developed to understand these temporal changes at the continental scale. It documents how complex interactions between actors in conflict ultimately shape the duration and geography of violence. Rather than considering time, space and conflict networks separately, the new concept of spatial conflict life cycle integrates these three dimensions in a unique way.

This spatialization of armed conflicts over time explores the most fundamental factors that explain the geography of violence. Using a relational approach, we recognise that actors in conflict have a unique area of operation and can engage in alliances or rivalries with other actors. This geography and conflict networks can change rapidly as conflicts erupt across the continent (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The spatial conflict life cycle is at the intersection of space, time, and networks

Source: authors.

Measuring conflict shifts

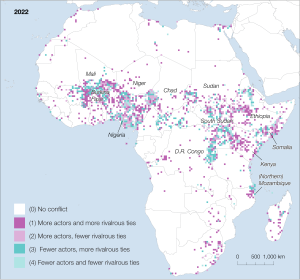

The analysis of spatial conflict life cycles builds on a new indicator that describes whether African regions have a higher number of violent actors and a higher proportion of rivalrous ties than in the previous year (Figure 2). This Spatial Conflict Life Cycle indicator (SCLCi) can use most conflict event datasets with locational, temporal, and actor information, such as the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED).

We examine how different regions transition from one conflict type to another as they go through the spatial conflict life cycle from 2000 to 2023. We are particularly interested in regions that experience sudden changes in the number of actors and rivalrous relationships, an evolution that signals the beginning or the end of a conflict. We also investigate what the most common sequence shifts are once a cycle is underway. This allows us to verify whether some cycles are more likely to occur than others in Africa.

The study of 179 000 violent events reveals that violence has both shifted and intensified over the last 23 years. Today’s conflict regions extend from the Sahel to the countries bordering the Gulf of Guinea (Figure 2), where the number of actors and rivalrous ties is growing . Violence is also particularly intense in Central and Eastern Africa. A secondary epicenter of violence has emerged in northern Mozambique following the Jihadist insurgency in Cabo Delgado Province in 2017.

Figure 2. Major hotspots of violence in Africa in 2022

Source: authors, based on ACLED data.

African armed conflicts are subject to regularities

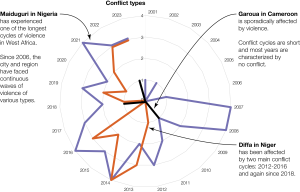

The analysis of 282 000 relationships suggests that both the number of actors and proportion of rivalrous ties follow an inverted U-shaped curve over time as conflicts emerge, expand, and end (Figure 3). Only a fraction of the possible conflict life cycles are observed on the continent, suggesting that African armed conflicts are subject to regularities in the way actors fight each other across time and space. More specifically, we found that cycles follow a generalized scenario in which certain conflict types characterised by more rivalrous ties are found at the beginning of a cycle and other types characterised by fewer rivalrous ties at the end.

These results suggest that, in the first stage, violence is initially concentrated within a few violent actors and the conflict environment is dominated by rivalrous relationships. Negative ties become increasingly important as the conflict develops, multiplying the number of actors in conflict without necessarily leading to many alliances. As conflicts start to de-escalate, the number of actors remains high, but alliances are gradually formed between actors, decreasing the proportion of rivalrous ties. Finally, in the last stage, the conflict is characterised by a small number of actors and a plurality of alliances, leading to the cessation of violence.

Figure 3. African conflicts are subject to regularities in the way actors fight each other

Source: authors

How the conflict life cycle affects cities and regions

Variations in the duration of life cycles have major implications for cities, as in the Lake Chad basin (Figure 4). Some cities located close to the epicenter of violence like Maiduguri in northern Nigeria have been affected by continuous episodes of violence, both from government forces and Jihadist groups. As a result, Maiduguri’s still ongoing conflict life cycle is the longest recorded on the continent, lasting 18 years.

Figure 4. Conflict life cycle in the Lake Chad region, 2001-2023

Source: authors.

Cities located in the periphery of the insurgency have experienced rather different patterns of violence. In southeastern Niger, violence in Diffa has waxed and waned, as demonstrated by shorter life cycles that also started with a transition between ‘no conflict’ and ‘more actors and more rivalry’ between 2017 and 2023. Finally, some regions are only episodically affected by violence, such as Garoua in Cameroon, where violence has usually lasted no longer than a year.

Towards a place-based approach to conflict

The spatial conflict life cycle is central in moving toward more nuanced understandings of the ever-evolving geographies of conflict among policy makers. In a region confronted by rapidly changing conflicts, mapping where violence emerges, spreads and dissipates should help design space-based policies that are mindful of the local factors that encourage people to turn to violence.

If conflicts have a life cycle, then policy response should be tailored to the stages reached by each conflict. The recent history of the Sahel suggests that heavy-handed responses from military forces are often counter-productive when violence is dispersed and of low intensity, while they remain indispensable in regions where an insurgency is in full bloom. If policymakers can identify the conflict life cycle stage in an area, they can better anticipate how the conflict will evolve through the life cycle’s series of theoretical steps. Likewise, with this knowledge, policymakers can focus their efforts around effecting the conditions for the transition to no conflict. In particular, such knowledge can help anticipating political decision and action.